According to shipping data provider eeSea, as of last Friday, the number of container ships waiting to berth near Shanghai and Ningbo was more than double that of the Port of Los Angeles/Long Beach (67), at 154!

The number of container ships berthing near Shanghai and Ningbo has surged in recent weeks, with a total of 74 vessels waiting to berth outside the Port of Ningbo Zhoushan, totaling 306,538 teu, a 48% increase in just one week.

Whether due to excessive export volumes, typhoon weather, or the new crown epidemic, increasing congestion at ports is another uncertainty for trans-Pacific trade.

Congestion at Chinese ports has slowed export flows, which is bad news for U.S. importers, but it may temporarily relieve pressure on the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach.

In June, Yantian port operations were severely limited by the outbreak, and the number of ships berthed in California’s San Pedro Bay was reduced. The problem facing California ports is that this temporary relief is quickly followed by a significant delay in the arrival of cargo.

What you want is more stability, not these fluctuations,” said Simon Sundboell, founder of eeSea, in an interview. I think what everyone is worried about is that the volatility will become more dramatic. When the supply chain is already so tight, all the unexpected events can be the cause of congestion.”

In pursuit of high freight rates, a large amount of capacity has been shifted to China-US routes

A major cause of supply chain congestion on both sides of the Pacific is that there is limited land transportation capacity (terminals, trucking, rail transportation, warehousing), but very flexible transportation capacity on a single ocean route.

Although the number of ships is limited globally, operators can move ships to where they are most profitable. Trans-Pacific trade is particularly lucrative now: spot prices including premiums can be up to $20,000/FEU.

These vessels are ultra-mobile,” Sundboell said. What is happening now is the opposite of what has plagued the industry for the past 20 years. Five years ago, people were asking: How can trans-Pacific rates drop from $2,000 to $1,500 (per FEU) in just six days? You could move a ship from one place to another and suddenly after there were more ships, the price war and freight rates went down.

“Now we’re seeing the opposite.” He said. As ship operators add capacity to the transpacific, congestion increases, delays rise and shippers’ incentives to pay insurance premiums are supported, keeping consolidated freight rates at record highs.

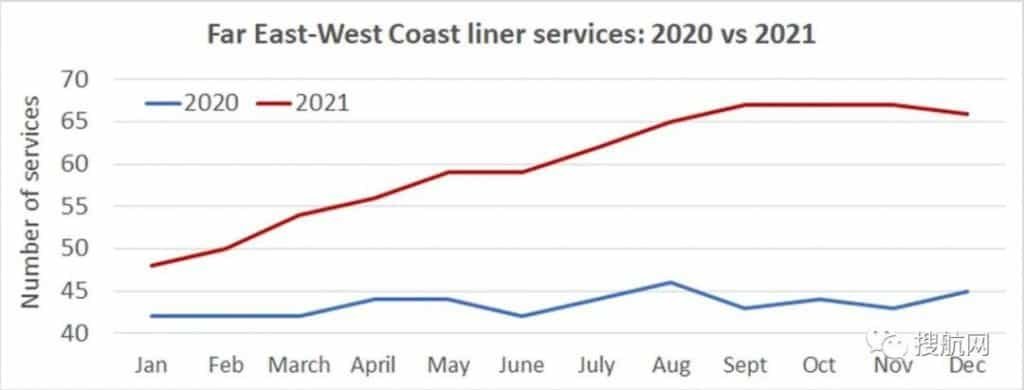

The number of services on the Far East-West Coast route has surged from 48 in January to 67 this month, according to eeSea. By comparison, the number of services on this route remained fairly constant at 42-46 vessels last year.

In addition, vessels were drawn from other routes as extra loading vessels (vessels performing one-time voyages). In some cases, multiple temporary vessels made multiple round trips, with extra loading vessels mixed with scheduled services.

Sundboell said, “We’re definitely seeing shipping lines pulling vessels out of the Asia-Middle East service and the Asia-Africa service and putting them into the trans-Pacific service.”

“Whether it’s as an extra loading vessel for a one-time round trip or whether it becomes semi-permanent, I don’t even think the shipping companies know themselves right now, they’re just ‘playing the market’. If it makes more economic sense to put a ship from the Middle East on the trans-Pacific route, they will do it, whether it’s for a month, three months, or six months. That’s why no one knows what the network will look like in six months.”

Smaller and smaller ships on the trans-Pacific route

Another reason for the increased congestion in trans-Pacific traffic: not only are there more ships, but the ships are getting smaller, which means more ships are needed to carry the same teu of the container.

According to eeSea data, the average capacity of ships on the Asia-US West Coast service in January was 8,601 teu, compared to 7,125 teu currently, a 17 percent drop.

American Shipper recently analyzed the average capacity of vessels currently drifting in or near Southern California anchorages and found a similar decline compared to the first quarter mooring peak on Feb. 1: from 8,060 teu to 6,184 teu, a 24 percent drop.

“The smaller the average capacity (size) of a vessel, it definitely slows down further,” Sundboell said.

Some operators are adding trans-Pacific capacity by buying vessels on the secondary market or chartering them on the charter market, and most of the vessels available for purchase or charter in 2021 are in the smaller category.

The practice of shipping companies shifting capacity from other routes also pulls down the average vessel capacity, as those routes use mostly lower capacity vessels. “The reason smaller vessels are coming into port is that they are moving them from the Middle East and Africa trade,” Sundboell said.

How is the congestion going to end?

Vessel operators can put as many ships as possible on the trans-Pacific routes to chase record spot rates, thus leaving other routes in a capacity shortage. Eventually, however, the imbalance should correct itself.

Sundboell explained, “It’s a self-balancing way of saying that if ships are removed from other routes, freight rates on those routes will rise to levels that will attract ships back.”

In the first quarter, when the anchorage near the Port of Long Beach in Los Angeles was “congested,” shipping lines were unable to call enough ships back to Asia in time to load cargo, so they had to cancel a large number of sailings (empty ships) to ease the congestion in the second quarter.

Given the current extreme ship waiting at berth situation in China and Southern California ports, the possibility of another blank sailing scenario in the fourth quarter is a worrisome prospect for importers.

Lack of predictability in route service

Even companies like eeSea, which tracks empty ship sailings, cannot be sure what will happen in the fourth quarter.

In the first half of 2020, when shipping lines stopped sailing due to a drop in demand caused by the epidemic blockade, they announced canceled sailings months in advance, sending an important signal to the market. This year there was much less noticeable, as the blank sailings were caused by congestion rather than a drop in forwarding demand.

According to Sundboell, “There were only eight blank sailings on the Asia-US West route in November and only three in December, but this is because the shipping lines have not yet issued notices. We only enter blank sailings into our system once they have been confirmed by the shipping lines. It’s become more erratic in terms of capacity and route service forecasts.”

I think this is exactly why shippers are frustrated. Shippers hate being forced to get used to ships always being 10 days late, or they don’t even know when the ship is coming.