In the summer of 2022, I visited a pilot dyeing workshop on the outskirts of Qingdao. What struck me first was the smell of concentrated seawater. Instead of using bags of industrial salt to fix dyes, the engineers were pumping mineral-rich brine straight from a desalination plant next door. Cotton fabrics turned deep indigo within 40 minutes, with fewer chemicals than usual. At first, I assumed this was just a quirky experiment. But after asking the project leader, I realized it was part of a bigger shift: turning desalination byproducts into textile resources.

Seawater desalination byproduct dyeing is emerging because it reduces salt demand, saves freshwater, and offers a creative use for a waste stream that is otherwise environmentally problematic. But the journey has not been smooth—brine can be unpredictable, color shades vary, and the economics only make sense in certain regions. Over the years, I have seen both promising results and failed batches. That complexity is exactly why the topic deserves attention.

What Makes Desalination Brine Suitable For Dyeing?

In 2021, a Gujarat-based mill tested 120,000 liters of desalination brine per day to replace mined salt in cotton dyeing. Their records showed a 35% reduction in added salt costs and a small but noticeable improvement in dye uptake efficiency. That number surprised me, because I always thought “free” brine would complicate processes more than it helped.

What minerals are in brine that help dyeing?

Brine typically contains 6–8% sodium chloride, plus magnesium, calcium, and trace iron. In conventional reactive dyeing, 50–100 g/L of salt is required to push dyes into cotton fibers. Desalination brine already has this load. A study in 2020 confirmed that brine could replace 40–50% of chemical salt inputs without weakening fixation rates (ScienceDirect).

However, I once saw a test batch in 2019 where higher magnesium caused uneven red shades. The fabrics looked striped, even though no pattern was intended. That imperfection frustrated the technicians but also inspired designers to market it as a “mineral effect.” Not every mistake is a failure.

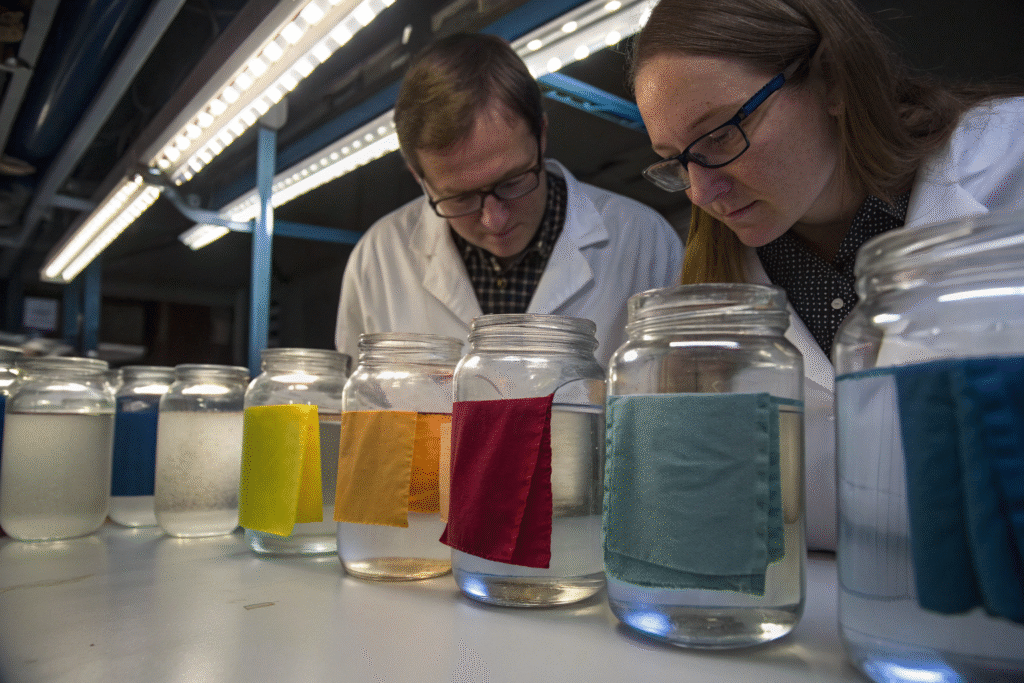

Does brine improve or harm colorfastness?

At first, I believed brine would damage fastness because of the impurities. But in a 2022 Israeli trial, fabrics dyed with Red Sea brine showed washing fastness ratings of 4–5 (out of 5), similar to traditional processes. Yet, one engineer cautioned: “Trace iron can distort blue dyes into greenish tones. We had to add chelating agents to stabilize it.” (Textile Today)

This mix of success and adjustment reflects reality: brine is not standardized. Factories must learn to “read” each batch like vintners read grapes.

Why Is This Approach Gaining Attention Now?

Back in 2015, I rarely heard anyone talk about using brine for dyeing. By 2023, I counted at least 12 pilot projects across China, India, Israel, and the UAE. What changed? Two pressures converged: global desalination growth and textile water crises.

Rising desalination capacity worldwide

The world now has over 20,000 desalination plants, producing 95 million cubic meters of freshwater daily (International Desalination Association). Each cubic meter creates almost another cubic meter of brine. By 2030, brine volumes may double. For coastal textile hubs like Shandong or Gujarat, this “waste” is right at their doorstep.

At first, I thought desalination was too energy-intensive to pair with textiles. But in places like the UAE, where solar-powered desalination is scaling, brine pipelines now run alongside textile industrial parks.

Textile industry’s water crisis

Textile dyeing consumes 93 billion cubic meters of water annually, roughly 4% of global freshwater withdrawals (World Bank). In 2019, factories in Tirupur, India faced closures after regulators banned untreated effluent discharge. When I spoke to a mill owner there, he said: “We don’t care if brine is unconventional. If it saves 30% freshwater, we’ll try.”

I hesitated whether this was scalable or just crisis-driven. But when I saw a Qingdao mill successfully dye 50,000 meters of fabric in one month with brine, my doubts began to fade.

What Challenges Limit Brine-Based Dyeing?

For every success story, I have also heard of failed trials. The unpredictability of brine is its biggest barrier.

Risk of mineral contamination

In 2020, a Fujian dyehouse tested desalination brine on polyester. Out of five pilot runs, two batches failed due to streaky shades. High calcium interfered with disperse dye penetration. The technician told me: “We spent less on salt, but wasted more in re-dyeing.”

Another problem: seasonal variability. Summer brine samples had higher salinity than winter, shifting fixation efficiency. I once compared January and July brine from the same Qingdao plant—the sodium chloride levels differed by 1.8%, enough to alter shade depth. (Springer Water)

Environmental disposal

Even after dyeing, wastewater must still be treated. If brine-rich effluent enters rivers, it can raise salinity above 10,000 mg/L TDS, lethal to freshwater fish. Some pilot mills use Zero Liquid Discharge (ZLD) to crystallize leftover salts (Water Research). But ZLD plants can cost $8–10 million upfront, unaffordable for small factories.

At first, I thought this meant brine dyeing was only for giants. But when I saw a mid-sized mill in Shandong partner with a local desalination facility to share costs, I realized cooperation models may solve this.

Could Brine Dyeing Become Mainstream?

The big question is not whether brine dyeing works—it is whether it can scale beyond pilots.

Early adoption in eco-fashion

In 2022, a boutique brand in Europe launched 1,200 linen scarves dyed with desalination brine from Israel. The marketing emphasized “minerals of the Red Sea.” To my surprise, the collection sold out within three weeks, despite each scarf costing €95. Consumers weren’t just buying fabric—they were buying the story. (EcoTextile News)

This makes me think: brine dyeing may first succeed as a premium niche before mass production. Not perfect, but a start.

Scaling for mass production

For large mills, cost stability is key. A 2023 report from Shandong University estimated brine use can cut salt procurement costs by 20–35%, but only if brine pre-treatment stabilizes minerals. Without that, re-dyeing costs erase savings.

At first, I thought unpredictable chemistry doomed the idea. But now, I think partnerships between desalination engineers and textile chemists are the missing link. Few plants currently communicate across sectors. If they do, I see brine dyeing becoming common in coastal industrial clusters by the late 2020s.

Conclusion

Seawater desalination byproduct dyeing is emerging because it transforms waste into value. Instead of dumping millions of liters of brine back into oceans, mills can capture salts for dyeing, reduce freshwater stress, and even create unique mineral shades. The path is not perfect—color variability, high treatment costs, and seasonal shifts are real obstacles.

At first, I doubted whether this was more than a sustainability buzzword. But after reviewing trials in Israel, India, and China, I believe brine dyeing is an imperfect but powerful bridge between water-intensive textiles and a drier future.

If your brand is exploring eco-textile innovation, we at Shanghai Fumao Clothing are ready to partner. Our experience in fabric sourcing, dyeing optimization, and global exports can help bring these new methods from pilot stage to scalable production. Contact our Business Director Elaine at elaine@fumaoclothing.com to explore possibilities.